This content was originally published on OldHouseOnline.com and has been republished here as part of a merger between our two businesses. All copy is presented here as it originally appeared there.

By James C. Massey and Shirley Maxwell

Since before written time, windows have functioned as openings in buildings to admit light and air, while visually relieving the expanse of wood or masonry walls with the tracery of muntins and the lightness of glass. Historically, however, there are many kinds of windows that pop out of buildings, defying wall planes or rising from rooflines to add delightful interest to an elevation even as they gain in practicality. Here we’ll take a look at three of the most common window projections-dormers, bays, and turrets-and how they have contributed to the design of houses over the course of three centuries.

Dormers

Ordinary? Well, yes. Commonplace? Certainly. Still, the dormer window must rank as one of the all-time great inventions in house building. Even in the early 18th and 19th centuries, they were not universally used (all that dark attic area going to waste except for storage), but frame a window into the roof and-presto!-you have light and ventilation, and livable, usable space. A dormer adds a nice architectural touch to the house design as well. Plain shed-roofed dormers like those in the little 18th-century cottage in Haddonfield, New Jersey (center, left), are the most basic type. Some early dormers might also be known as lucernes or lutherns. Dormers became one of the distinguishing features in fine Georgian houses, such as the 1762 Derby House in Salem, Massachusetts (top), where they provide livable attic space and an architectural grace note to the composition. The end dormers of the set of three have gable roofs, while the center one has a fancier arch-head roof. Naturally they are smaller than the downstairs windows, as befits their rooftop status. At Carter’s Grove near Williamsburg, (1750-1755), one of the great James River plantations and now a Colonial Williamsburg museum, a tall roof sports a notable array of hipped dormers (center), tall and narrow in the Virginia tradition. They are indeed handsome but were actually added to the house during its upscale restoration into an elegant country house in the early 20th century-a common practice then that continues to this day.

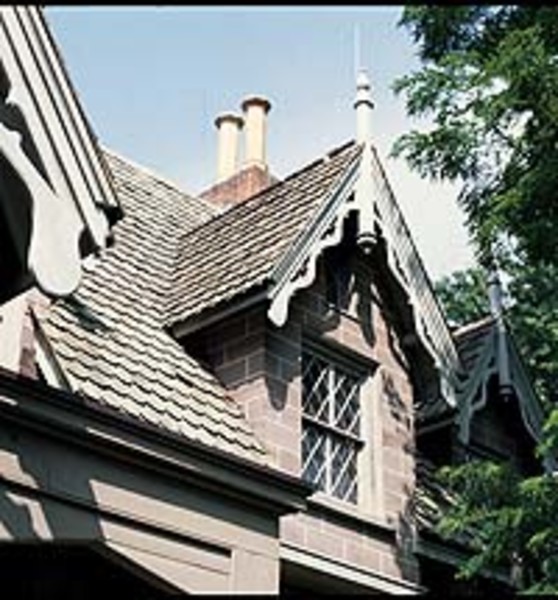

In the Victorian era, dormers became much more ornamental, as is the case with the Gothic Revival Hermitage in Ho-Ho-Kus, New Jersey, on the opposite page. Note that the dormer rises directly from the wall of the house and is framed in the same brownstone ashlar as the house itself, probably derived from French tradition. To the sides are smaller dormers, raised up on the roof in the normal manner. These dormers are highly enriched with scrollwork and a pinnacle, as well as diamond-paned windows. Actually, the Hermitage as we see it is an 1848 remodeling by architect William Ranlett of an 18th-century Dutch house. As at Carter’s Grove, such updatings may be found at any period. In the early 20th century, the bungalow became one of the basic American house types, one frequently defined by dormers that provide light and space under a broad, sloping roof over a single story. This bungalow in Eugene, Oregon (center, right), has triple windows under a high and broad stuccoed gable, which contributes substantially to making a more livable second floor. Some bungalows feature as many as six windows in one wide, linear dormer. In Colonial Revival houses, double dormers became common, with the same advantage, although historically such dormers were not found before the Greek Revival era.

Bay Windows

The basic American bay window has been in common use from the Victorian period to this day. It’s a simple, very functional way to increase light, ventilation, and view in a room. Most bays are three-sided or curved, although there are many variations and some special terms that apply. Their use arose in Europe in the medieval period and Renaissance, mostly in large structures and mansions, not in the simple houses of common folk. The classic American bay window may be one story or two, but it rises from the foundation, as do most examples here. The exception is the little rectangular Gothic Revival window (center, right) that is more properly called an oriel, as it does not extend to the ground. The Baltimore row house (center) is a bow-front house, as the bow extends from top to bottom. The bow-front fashion dates to the Federal period. The other bow (right) in Old Town Alexandria, Virginia, is correctly a bow oriel, as it is limited to the second story. The house at top is a classic Sears ready-cut (Modern Home, #306; 1911-1917) in Strasburg, Virginia. Its prominent two-story bay window is topped by a large pediment. In the Garden District of New Orleans (center, far left) is an unusual Queen Anne house with a four-window bay and a center panel between the pairs of windows. The upper sash are fancy small panes and the lower one a single pane, a typical configuration of the period. The bay is surmounted by a projecting balcony on consoles, an unusual feature. In a 1930s bungalow in Reno, Nevada (center, far right), the normal three-sided bay gains visual interest through cobblestone walls and steel casement sash. The popularity of bay windows continued through the 20th century, in everything from bungalows to Colonial Revival houses.

Turrets

The turret, common in the late Victorian, Queen Anne, Eastlake, and Romanesque house, carried the advantage to the maximum. It is a circular or octagonal bay attached generally to a corner of the house and frequently, though not necessarily, rising above the roofline to create an extra story, as in the circa 1896 house in Laurins, South Carolina, by George Barber, shown at right. Barber’s Houses by Mail designs most often are fanciful and highly ornamented; this octagonal example is a model of its kind. Turrets arose in the medieval period in castles and churches, usually for stairs or as watchtowers, in which case they could also be called Žchaugettes. This Victorian house in Washington, Georgia (left, center), has a less common, square corner turret, as well as a fine four-window rectangular bay.