This content was originally published on OldHouseOnline.com and has been republished here as part of a merger between our two businesses. All copy is presented here as it originally appeared there.

Red brick Romanesque in Savannah, Georgia (1887)

While the Gothic soared, the Romanesque hunkered down, suggesting not lightness of being but structure and solidity. Massive arches broke walls of stone. Corner towers appear almost fortress-like.

The U.S. first saw use of the revival style during the 1850s. Think of the original building of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington-“the castle“ by James Renwick-or of Holy Trinity Church in Philadelphia by John Notman. But the style became something new when it was adopted for residential use by Boston architect Henry Hobson Richardson, one of the greatest 19th century architects.

Copshaholm, South Bend, Indiana (1895)

At first Richardson used Romanesque for public buildings like Boston’s famous Trinity Church. Then he took the monumental forms and scaled them for city residences. His adaptation culminated in the unique 1885 design for Chicago’s Glessner House, where an austere, flat stone façade gives way to towers on the hidden courtyard. Inside, the layout is a proto-modern open space built around the idea of the medieval great hall.

The buildings referred to as Romanesque are almost always masonry. Romanesque forms do occur in Victorian wood-framed and shingled buildings, but these are usually classified with the Shingle Style.

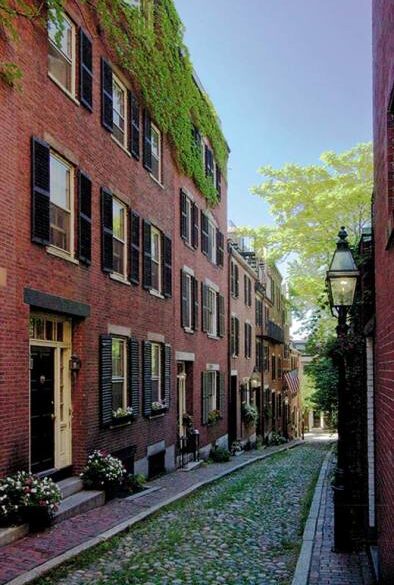

Richardson’s much-admired and -publicized designs were adapted by other architects, including some who had worked in his firm or succeeded him after his untimely death: Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge and John Wellborn Root are well known for their architecture. The “Richardsonial Romanesque“ style was used for row houses from New York and Philadelphia to Chicago and Kansas City, and for all types of structures across the Midwest.

Hallmarks of Romanesque Buildings

- Massive, structural appearance, almost always in masonry, often undressed (rough)

- Masonry of different types often appeared together: brick with stone, brownstone ashlar with granite lintels and carved brownstone ornament

- Arched openings, arcaded windows, arched porte-cochere, etc.

- Tower or turret with conical roof

- Bold ornament, including oversized carvings, Celtic twining motifs, belt courses, web arches, carved figures (including cherubs, griffins, and lions), and corbels at cornices

- Queen Anne details such as a bay or oriel, divided windows, or decorative panels

The Romanesque Interior

Rooms inside are often as bold as the exterior, with arches, massive staircases, paneled walls, huge fireplaces, and carvings. Richardson’s houses centered on a living hall, off of which the staircase and parlor flowed. Dark oak was common.

Mid-Victorian, Jacobean, and Aesthetic Movement furniture mingled. Rooms in the 1890s were often decorated in historical revival styles, from “Colonial“ to French Beaux Arts. Chicago’s Glessner House was decorated with Morris & Co. wallpapers and textiles.

Recommended Reading

Living Architecture: A Biography of H.H. Richardson

By James O’Gorman (Simon and Schuster, 1997)

A study of the architect (1838-1886), with 150 photos to show his work. It is apparent that Richardson was both a talented interpreter of historical architecture and an early modernist thinker.

H.H. Richardson: Complete Architectural Works

By Jeffrey Karl Ochsner (MIT Press, 1985)

A complete catalog of his works, built and unbuilt, surviving and demolished, including offices, colleges, stores, libraries, churches, railway stations, and residences. Illustrated with sketches, plans, and interior and exterior photographs; maps and addresses are supplied for buildings which survive. Eight supplemental entries round out the paperback edition.

Henry Hobson Richardson: J.J Glessner House, Chicago

By Elane Harrington (Distributed Art Pub Inc., 1993)

A 60-page monograph on the house with photos by Hedrich Blessing. Out of print.

Frank Furness: The Complete Works

By George E. Thomas, et al (Princeton Architectural Press, 1997)

Exhaustive monograph on the work of Philadelphia architect Furness, who worked in Stick, Reformed Gothic, exotic, and Romanesque styles in the same era as Richardson. 600 photos and drawings.

The Houses of McKim, Mead & White

By Samuel G. White (Universe, 2004)

Houses by preeminent architects of Richardson’s era (and the generation beyond). From 1879 to 1912, the firm designed over 300 residential commissions in places like Newport, the Hudson Valley, and Long Island. Exteriors and rooms inside are shown.

The Aesthetic Movement

By Lionel Lambourne (Phaidon, 1996)

The English art movement of the 1880s and 1890s that had such great impact even in America. The book is monumental but very readable, starting with the Japonisme fad and moving on to Whistler, Ruskin, Oscar Wilde, Godwin, even Mackintosh. Lavish.